Pantikapaion

Publication date: 26.05.2025

- Region:

- Eastern Europe

- Timespan:

- 7th BC — 4th AD

- Coordinates:

- 45.36

36.47

PANTIKAPAION — one of the largest ancient cities in the Northern Black Sea region and the capital of the Bosporan Kingdom. Pantikapaion is one of the most ancient cities of Russia.

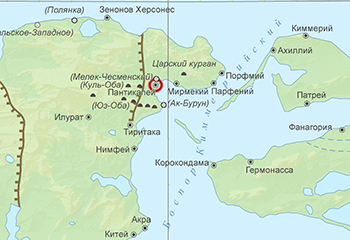

Fig. 1. Map of European and Asian Bosporus

.jpg)

Fig. 2. Pantikapaion. General View from North-East on the Upper Plateau of the ‘First Throne’ (‘New Upper Mithridatic’ Excavation Site) and the Central Part of the Settlement

_%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B7.jpg)

Fig. 3. V. D. Blavatsky and N. I. Sokolsky on their way to Taman

.jpg)

Fig. 4. I. D. Marchenko speaks to Kerch schoolchildren about excavations on Mount Mithridates

Fig. 5. Pantikapaion. Plan of ‘Prytaneion’ and a Building, Discovered by K. E. Dumberg. 1 — Border between excavation areas; 2 — Stone walls and bases of columns; 3 — Rock terraces; 4 — Floor surface

.jpg)

Fig. 6. Restoration of ‘Prytaneion’ by Anastylosis Technique. 1975

Fig. 7. Pantikapaion. ‘New Upper Mithridatic’ Excavation Site. Pottery from the Burnt Layer (mid-6th Century BC). 1 — East Greek Pottery; 2 — Anatolian Painted Pottery

Fig. 8. Pantikapaion. Map of Fortifications of the First and Fourth Construction Periods

Fig. 9. Pantikapaion. First Apollo Temple. 510–490 BC

Fig. 10. Pantikapaion. Western Plateau. Central and Northern Central Excavation Sites. Map and Axonometry of the Public Complex, Consisting of Tholos and Fortifications. 515–480 BC

.jpg)

Fig. 11. Arrowheads of Scythian Type from Layers of Destruction (Upper and Western Plateaux). Circa 480 BC

Fig. 12. Pantikapaion. ‘New Upper Mithridatic’ Excavation Site. Map of Fourth Construction Period Buildings with Architectural Complex as Part of Fortification Line

Fig. 13. Pantikapaion. ‘New Upper Mithridatic’ Excavation Site. Found Items Decorated in Scythian Animal Style. First Half of 5th Century BC

Fig. 14. Pantikapaion. Second Apollo Temple. Façade Scheme. 450–445 BC

Fig. 15. Pantikapaion. Spartocids’ Basileia. Central Building and Palace Temple

PANTIKAPAION (Ancient Greek: Παντικάπαιον, Latin: Panticapaeum) (7th century BC — 4th century AD) — one of the largest ancient cities in the Northern Black Sea region and the capital of the Bosporan Kingdom, one of the most ancient cities of Russia.

Topography and Location

The ancient settlement was located on the three peaks and slopes of a hill known as ‘Mount Mithridates’ since the late 18th century. Its easternmost terrace (91 m above sea level), marking the point where the steep eastern slope descends toward the Kerch Bay, is called the ‘First Throne of Mithridates’ (Fig. 1). Its central elevation is known as the ‘Rocky Outcrop’, and its western one as the ‘Second Throne of Mithridates’. The eastern and western peaks are crowned with rocky outcrops, where well-preserved regular horizontal and vertical chisel marks from the bedding under the ancient ashlar masonry of the foundation can still be seen on the surfaces. It is these chiselled surfaces that have come to be known as the ‘Thrones’ or ‘Seats’ of King Mithridates. The inhabited area of the ancient city also included the plain to the north. The estimated area of the ancient settlement is about 126 hectares (Fig. 2).

Written Sources

According to Stephanus of Byzantium, Pantikapaion took its name from the Pantikapes river flowing in the area (now known as the Melek Chesme or Primorskaya River) [Latyshev 1890: 264].

According to Strabo, the city was founded by settlers from Miletus. The brief description of Pantikapaion left by the author reads, “Panticapaeum is a hill, inhabited on all sides in a circuit of twenty stadia. To the east it has a harbour, and docks for about thirty ships; and it also has an acropolis” (Str. VII, 4, 4). Important information about the terraced layout of the acropolis is provided by Appian (Mith. 111).

History of Discovery and Study

The earliest surveys of Pantikapaion began in 1816. In the 1820s Paul Du Brux, a French royalist émigré in Russian service, published a hand drawn layout of the site, together with a description of its architectural remains [Du Brux2010; Tolstikov 2010a: 463–470]. The Belgian traveller F. Dubois de Montpéreux and the Kerch city architect A. Digby (the younger) also published site layouts of scholarly value.

The year 1830 was marked by the discovery of an exceptionally rich burial in the Kul‑Oba kurgan. While this event signalled the birth of classical archaeology in Russia, it unfortunately also marked the beginning of a ‘gold rush’, which gave rise to generations of the so-called ‘lucky’ antiquities looters based in Kerch. In addition to the extensive looting, the intensive activities of an emerging circle of archaeologists conducting frequent and often unsystematic ‘excavations’ within the city site and its necropoleis have left us with fragmented information about the ancient city (R. de Skassi, I. P. Blaremberg, K. R. Begichev, A. E. Lyutsenko, F. I. Gross, K. E. Dumberg, V. V. Shkorpil).

The initial plan for the archaeological study of Pantikapaion was proposed by the director of the Kerch Museum of Antiquities, Yu. Yu. Marti (1874–1959). Conducting salvage excavations in Kerch, in the courtyard of building no. 10 on Teatralnaya Street, he discovered a long segment of rusticated ashlar masonry from the northern city wall of the Hellenistic period, preserved within an old water supply tunnel dating from the late 19th century. The fortifications of the Pantikapaion acropolis, uncovered in 1930–1931 along the southern and southeastern slopes of the ‘First Throne’, should also be mentioned among his most important discoveries. Marti’s excavations were interrupted by the Great Patriotic War of 1941–1945.

In 1945, V. D. Blavatsky, Professor of Moscow State University, initiated a joint Bosporan Expedition, which was organised by the Institute of the History of Material Culture of the USSR Academy of Sciences, as well as the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. This marked the beginning of regular research at Pantikapaion. From 1945 to 1958, researchers developed and implemented the fundamental methodological principles for excavating a multi-layered ancient site while formalising field documentation. Indeed, an entire generation of specialists of the so‑called Moscow School of Classical Archaeology (N. A. Sidorova, N. M. Loseva, I. D. Marchenko, A. K. Korovina, I. B. Zeest, D. B. Shelov, G. A. Koshelenko, N. P. Sorokina, N. I. Sokolsky, V. S. Zabelina, and others) (Fig. 3)

was formed and qualified by V. D. Blavatsky.

From 1959 to 1976, study of the site was continued by an independent Bosporan Expedition of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts headed by I. D. Marchenko (Fig. 4).

A discovery made at the ‘New Esplanade’ excavation site was one of the notable results from this period. Here a substantial area of Late Archaic construction dating to the late 6th — first half of the 5th century BC was uncovered — the earliest phase identified up to that point in the research. Between 1962 and 1972, researchers investigated the southern part of a monumental complex with a peristyle in the Doric order. I. D. Marchenko named it the ‘Prytaneion’ (from the Ancient Greek: πρυτανεῖον — the meeting place of the prytaneis, members of the boule, the council governing the polis) [Marchenko 1968; 1984]. Later archival research revealed that the northern half of this complex, which is located on a lower terrace, had been studied by K. E. Dumberg in 1896–1899 (Fig. 5).

It was Marchenko who enabled the first and currently only on-site reconstruction of part of the building’s colonnade, which was carried out in 1975 by restoration architects B. L. Altshuller and A. A. Voronov using anastylosis (Fig. 6).

To this day, this unique colonnade of the 2nd century BC is rightfully considered one of the symbols of Kerch.

Since 1977, the Bosporan Expedition of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts has been under the direction of V. P. Tolstikov. Under his lead, researchers uncovered — for the first time — a layer and structures dating from the last quarter of the 7th to the early 6th century BC at the ‘New Upper Mithridatic’ excavation site.

Chronology and Stratigraphy

The founding of the Milesian apoikia (from the Ancient Greek: ἀποικία — the colony) on the upper plateau of Mount Mithridates dates to 615–610 BC. Excavations of 2024 uncovered the remains of buildings from the First Construction Period. This phase can be dated by fragments of Chian and Clazomenian amphorae, as well as sherds of East Greek pottery — bird cups and dinos vessels decorated in the Wild Goat style. These fragments were found in a conflagration layer up to 1.4 m thick covering the remains of the foundation and socle of a massive defensive wall that had been constructed during the Second Construction Period, around 600 BC. In some areas, the wall overlapped segments of masonry from the First Period structures.

In addition to the earliest ceramic finds mentioned above, the burnt layer also contained a highly representative assemblage of ceramics from the first half of the 6th century BC, including amphora fragments, East Greek pottery, early examples of Attic black-figure vessels, and sherds of handmade Kizil-Koba pottery. Moreover, this Second Period layer, dating to 600–550 BC, yielded previously undocumented fragments of Anatolian (Phrygian) painted pottery (Fig. 7).

Scythian-type bronze arrowheads, the hilt of an iron akinakes (short sword), and human bones found in the same burnt layer point to a military attack by nomads. However, the discovery of the stone socle of a new structure on the levelled surface of the burnt layer indicates a renewal of settlement life during the Third Construction Period (545–520 BC).

The Third Construction Period is associated with circular pit structures found on the western plateau (Central excavation site) and measuring 3.0 to 3.5 m in diameter. These are the remains of temporary semi-dugout dwellings dating to the third quarter of the 6th century BC. Their presence indicates the beginnings of the lower-lying territory development to the west of the ‘First Throne’ [Tolstikov 1992: 45–99].

The monumental architectural complex constructed on the western plateau consisted of multi-chamber buildings and a tholos, which may have served as a prytaneion, as well as a system of streets linking these structures. The undoubtedly public function of this ensemble is indicated, in particular, by the discovery of fragments of a unique Clazomenian bath inside the multi-chamber ‘Complex I’. The fragments are decorated with relief friezes depicting racing chariots, palmettes, lotus flowers, and an ovolo ornament. All of this attests to a significant westward expansion of the settlement and its urbanisation during the Fourth and Fifth Construction Periods (520–480 BC) [Tolstikov 2017a: 17–19] (Fig. 8).

The years 510 to 495 BC mark the likely construction of a peripteral temple dedicated to Apollo the Healer within the temenos on the upper plateau. The temple is executed in the Samian style of the Ionic order [Tolstikov 2010b] (Fig. 9). The probable existence of such a temple was first proposed in the 1950s by V. D. Blavatsky based on the torus mouldings and plinths — essential components of column bases — which he had been discovered in 1945 [Blavatsky 1957: 28–33]. Notably, the first series of Pantikapaion silver coins were minted in the same period as the temple construction.

An analysis of the evidence obtained during recent excavations suggests that Phase 3 of the Fifth Construction Period was interrupted around 480 BC by a new military conflict. A burn and destruction layer has been archaeologically documented in settlements on both sides of the straits (Fig. 1). It appears that the inhabitants of Pantikapaion took urgent measures to fortify the central area of the city, incorporating residential and public buildings into the defensive line in anticipation of a military threat. However, these precautions seem to have been largely ineffective. The architectural public complex with its tholos on the western plateau was destroyed (Fig. 10). Evidence of destruction and localised fires, along with concentrations of Scythian-type arrowheads, is also recorded on the upper plateau (Fig. 11, 12). The attack resulted in damage to the altars and other sacred structures located there, including the temple of Apollo. A marble three-section lamp of the so-called island type, and numerous votive offerings with dedications to patron deities that had been housed in the sanctuaries of the temenos from the first half of the 6th century BC to the 480s BC were also damaged. The remnants of these votive offerings, which included small fragments of pinakes and terracottas bearing graffiti, would later end up in the refuse deposits covering the ruins of buildings and the area of the northwestern slope of the upper plateau.

This catastrophe is further evidenced by a specific group of finds on the acropolis — namely horse harness details in the Scythian Animal Style (Fig. 13) — discovered for the first time at the site. All this suggests that the city was captured by the Royal Scyths. Like Olbia, Nikonion, Kerkinitis, and Nymphaion, Pantikapaion came under the so-called Scythian ‘protectorate’ [Tolstikov 2023]. If that is the case, then we may assume that from 480/487 BC, an authoritarian group of city rulers referred to by Diodorus as the Archaeanactids (D. S. XII, 31, 1) — or, according to an alternative reading of this designation proposed by F. V. Shelov-Kovedyayev, “those who refounded the polis” [Tolstikov, Shelov-Kovedyayev 2014] — was under the control of the leaders of the Royal Scyths for a period of 42 years, paying tribute to them and offering them precious gifts, wine, and similar.

The Sixth Construction Period (two phases: second quarter to mid-5th century BC) is marked by signs of regression in residential development on the western plateau, specifically a forced return to primitive, rectangular semi-subterranean dwellings dug into the ground. There is reason to believe that this temporary decline was due both to the need to pay tribute and, in part, to the costly reconstruction and partial renovation of the temple of Apollo in the Pantikapaion temenos, which began around the mid-5th century BC. During this construction work, which may have involved an Attic architect, previous Samian-type column bases were retained to save time and resources, while capitals and decorative elements of the entablature were executed in the more advanced Attic variant of the Ionic order (Fig. 14). It is worth noting that a similar combination of Samian-style bases and Attic-type capitals is documented for the architectural structures on the Athenian Acropolis [Tolstikov 2024].

The Seventh Construction Period (three phases: third quarter of the 5th century BC — 410 BC) is marked by a return to above-ground housing on the western plateau, including the construction of a residential building with stone-faced basement rooms (‘House A’). In Phase 3 (around 410 BC), the ‘House with the Andron’ was built. In the northeast corner room, a section of mosaic flooring has been preserved, along whose western, northern, and eastern edges we find a 0.85-metre-wide band of burgundy plaster that served as a base for the placement of reclining couches (klinai). The room functioned as a dining hall for male banquets (symposia). Ionic order was apparently employed in this monumental structure, as evidenced by stone bases. It is assumed that this architectural complex may have served as the residence of the first Spartocids — the new ruling dynasty of the Bosporan Kingdom [Tolstikov 2016].

In the Eighth Construction Period, during Phase 1 (the 370s BC), all of the aforementioned structures on the western plateau were demolished and their remains were overlain by a new fortified residence complex of the Spartocid dynasty — a basileia (Ancient Greek: βασίλειον — a palace) with a central building, the base of which covered an area of 1,025 m2. This building included a peristyle courtyard surrounded by a two-tiered colonnade, a 12-metre-deep well, and a water basin. Nearby there was a temenos with a palace-style antae temple in the Doric order [Tolstikov 2000]. The northwestern corner of the basileia complex was enclosed by a large two-story structure built into the rock massif, which had been hewn down to a height of 6 m, and featuring a peristyle courtyard [Tolstikov, Kuzmina 2011; Tolstikov 2016: 88–91]. The remains of this monumental ensemble on the western plateau recalls the account of Polyaenus, who wrote that the Bosporan dynast Leucon I ruled from 389/388 to 349/348 BC and had a residence in Pantikapaion, which the author referred to as a palace (Ancient Greek: ἡ αὐλή) (Polyaen. VI, 9, 2) (Fig. 15).

Archaeological evidence contains signs of destruction on the acropolis as a result of catastrophic earthquakes that occurred in the second quarter of the 3rd century BC. During the Ninth Construction Period (second half of the 3rd century BC) the basileia and acropolis structures underwent repairs and partial reorganisation. A fort featuring defensive and signal towers was built on the rock of the ‘First Throne’, together with a surrounding wall that utilised architectural elements, blocks, and fragments of sculpture taken from destroyed religious buildings (Fig. 16). The street network and water supply system were updated, with massive cisterns carved into the rock for the latter. The so-called ‘prytaneion’ was then built in the early 2nd century BC.

The final destruction of the main building of the basileia occurred during the Tenth Construction Period (last quarter of the 2nd century BC — mid-1st century BC), along with a change in the functional significance of the western plateau within the acropolis of Pantikapaion. During this time, a defensive line with a gate, a sallyport, and a bastion was constructed on the western plateau along a west-east axis. Traces of construction activity from the period of Mithridates VI Eupator’s rule can also be found in the preserved structures of the northern line of the basileia fortifications.

According to numismatic data, from 14 to 8 BC, Pantikapaion was referred to as Caesarea in honour of the Roman Emperor Augustus.

In the Eleventh Construction Period (late 1st century BC — early 2nd century AD), a section of the fortifications built during the previous period was repaired and reinforced. This period ends with the destruction of all these structures, with evidence of localised fires.

Phase 1 of the Twelfth Construction Period (mid-2nd — mid-3rd century) is marked by the construction of isolated monumental residential complexes with basement rooms on the western plateau, as well as a large rectangular reservoir for collecting water from the streets via ceramic aqueduct pipes. Phase 2 is characterised by a cessation of construction activity on the top of Mount Mithridates, with urban development shifting to a plain near the bay in the second half of the 3rd century [Tolstikov, Zhuravlev 2001].

From the 4th century onward, a necropolis began to form near the summit of the ‘First Throne’ of Mount Mithridates and continued to exist into the early medieval period.

Modern Status and Condition

The Ancient City of Pantikapaion Architectural and Archaeological Complex is a cultural heritage site of federal significance (registration number in the Unified State Register of Objects of Cultural Heritage of the Peoples of the Russian Federation: 911540360150006) managed by the Eastern-Crimean Historical and Cultural Museum-Preserve. The most valuable artifacts from the excavations at Pantikapaion are preserved in the State Hermitage Museum, the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, the State Historical Museum, and the East Crimean Historical and Cultural Museum-Reserve, as well as in other collections.

Fig. 16. Pantikapaion. Upper Plateau. Citadel of Acropolis. 210 BC — Early 2nd Century AD. Reconstruction

Bibliography

Blavatsky 1957 –– Blavatsky, V. D. “Stroitelʹnoe delo Pantikapeia po dannym raskopok 1945–1949 i 1952–1953 gg. [Building Activities of Panticapaion Based on Data from 1945–1949 and 1952–1953 Seasons of Excavations].” Pantikapeĭ. Materialy i issledovaniia po arkheologii SSSR. Vyp. 56 [Pantikapaion. Studies and Materials on the Archaeology of USSR. Vol. 56], edited by I. B. Zeest, Moscow: AN SSSR, 1957, pp. 5–95 (in Russian). Du Brux 2010 — Tunkina, I. V. (ed.). Diubriuks, P. Sobranie sochineniĭ [Paul du Brux. Œvres]. Saint Petersburg: Kolo, 2010 (in Russian). Latyshev 1890 — Latyshev, V. V. Izvestiia drevnikh pisateleĭ grecheskikh i latinskikh o Skifii i Kavkaze. T. 1 [Reports of Ancient Greek and Latin Authors about Scythia and Caucasus. Vol. 1]. Saint Petersburg: Tipografiia Imperatorskoĭ Akademii nauk, 1890 (in Russian). Marchenko 1968 — Marchenko, I. D. “Raskopki Pantikapeia v 1959–1964 godakh [Excavations at Pantikapaion. Seasons 1959–1964].” Soobshcheniia Gosudarstvennogo muzeia izobrazitelʹnykh iskusstv im. A. S. Pushkina. T. 4 [Reports of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. Vol. 4], edited by N. A. Sidorova, Moscow: Sovetskiĭ khudozhnik, 1968, pp. 27–53 (in Russian). Marchenko 1984 — Marchenko, I. D. “Raskopki Pantikapeia v 1965–1972 godakh [Excavations at Pantikapaion. Seasons 1959–1964].” Soobshcheniia Gosudarstvennogo muzeia izobrazitelʹnykh iskusstv im. A. S. Pushkina. T. 7 [Reports of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. Vol. 7], edited by I. E. Danilova, N. A. Sidorova, L. M. Smirnova, Moscow: Sovetskiĭ khudozhnik, 1984, pp. 3–27 (in Russian). Tolstikov 1992 — Tolstikov, V. P. “Pantikapeĭ — stolitsa Bospora [Pantikapaion: The Capital of Bosporus].” Ocherki arkheologii i istorii Bospora [Works on Archaeology and History of Bosporus], edited by G. A. Koshelenko, Moscow: Nauka, 1992, pp. 45–99 (in Russian). Tolstikov 2000 — Tolstikov, V. P. “Dvorets Spartokidov na akropole Pantikapeia (k probleme lokalizatsii, interpretatsii i graficheskoĭ rekonstruktsii) [Palace of Spartocids on Pantikapaion’s Acropolis: Localisation, Interpretation and Reconstruction].” Drevnosti Bospora. Mezhdunarodnyĭ ezhegodnik po istorii, arkheologii, ėpigrafike, numizmatike i filologii Bospora Kimmeriĭskogo. T. 3 [Antiquities of Bosporus. Annual Anthology of Works on History, Archaeology, Epigraphy, Numismatics, and Philology of the Cimmerian Bosporus. Vol. 3], edited by A. A. Maslennikov, Moscow: IA RAN, 2000, pp. 302–339 (in Russian). Tolstikov 2010a — Tolstikov, V. P. “Plan Polia Diubriuksa i arkheologiia Pantikapeia [Paul du Brux’ Plan and Archaeology of Pantikapaion].” Diubriuks, P. Sobranie sochineniĭ. T. 1 [Paul du Brux. Œvres. Tome 1], edited by I. V. Tunkina, transl. by N. L. Sukhacheva, Saint Petersburg: Kolo, 2010, pp. 463–470 (in Russian). Tolstikov 2010b — Tolstikov, V. P. “Khram Apollona na akropole Pantikapeia. Problemy datirovki, tipologii i periodizatsii [Apollo Temple in Pantikapaion Acropolis (Dating, Typology, Periodisation)].” Problemy istorii, filologii, kulʹtury [Journal of Historical, Phililogical, and Cultural Studies], no. 1, 2010, pp. 277–314 (in Russian). Tolstikov 2016 — Tolstikov, V. P. “Arkhitekturno-planirovochnaia sreda Tsentralʹnogo raĭona Pantikapeia kak istochnik po sotsialʹno-politicheskoĭ istorii Bospora [Architecture and Planning of Pantikapaion’s Central District as a Source on Social and Political History of Bosporus].” Ėlita Bospora i Bosporskaia ėlitnaia kulʹtura. Materialy mezhdunarodnogo kruglogo stola (22–25 noiabria 2016 g., Sankt-Peterburg) [Bosporan Elite and Its Culture. Papers of the International Round Table November 22–25, 2016], edited by V. Yu. Zuev, V. A. Khrshanovskiy, Saint Petersburg: Palatstso, 2016, pp. 77–92 (in Russian). Tolstikov 2017a — Tolstikov, V. P. “Ocherk gradostroitelʹnoĭ istorii tsentralʹnogo raĭona Pantikapeia v 7 — seredine 5 vekov do n. ė. [Essay on Building History of Pantikapaion’s Central District from 7th to mid-5th Century BC].” Drevneĭshiĭ Pantikapeĭ. Ot apoĭkii — k gorodu: po materialam issledovaniĭ Bosporskoĭ (Pantikapeĭskoĭ) ėkspeditsii GMII imeni A. S. Pushkina na gore Mitridat [The Earliest Pantikapaion. From an Apoikia to a City. Based on the Field Research of the Bosporan (Panticapaeum) Archaeological Expedition of the State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts on the Mount Mithridates], edited by V. P. Tolstikov, N. S. Astashova, G. A. Lomtadze, O. Yu. Samar, O. V. Tugusheva, Moscow: Pero, 2017, pp. 10–53 (in Russian). Tolstikov 2017b — Tolstikov, V. P. “Ocherk gradostroitelʹnoĭ istorii tsentralʹnogo raĭona Pantikapeia [Essay on Building History of Pantikapaion’s Central District].” Pantikapeĭ i Fanagoriia. Dve stolitsy Bosporskogo tsarstva [Pantikapaion and Phanagoria. Two Capitals of the Bosporan Kingdom], Moscow: GMII im. A. S. Pushkina, 2017, pp. 69–83 (in Russian). Tolstikov 2023 — Tolstikov, V. P. “Arkheologicheskie svidetelʹstva katastrofy 480–475 gg. do n. ė. v Pantikapee. Proshchanie s odnoĭ kontseptsieĭ? [Archaeological Evidence of the Disaster of 480–475 BC in Pantikapaion. Saying Goodbye to One Concept?].” Problemy istorii, filologii, kulʹtury [Journal of Historical, Phililogical, and Cultural Studies], no. 3, 2023, pp. 9–36 (in Russian). Tolstikov 2024 — Tolstikov, V. P. “Khram Apollona na akropole Pantikapeia. Novye materialy k vossozdaniiu oblika i istorii [The Temple of Apollo on the Acropolis of Pantikapaion. New Materials to Reconstruct the Appearance and History].” Drevnosti Bospora. № 29 [Antiquities of Bosporus. Vol. 29], edited by A. A. Maslennikov, Moscow: IA RAN, 2024, pp. 437–474 (in Russian). Tolstikov, Zhuravlev 2001 — Tolstikov, V. P., and D. V. Zhuravlev. “Novye dannye k topografii Pantikapeia pervykh vv. n. ė. [New Data on Topography of Pantikapaion at the Beginning of the 1st Millennium AD].” Bospor Kimmeriĭskiĭ i Pont v period antichnosti i srednevekovʹia: materialy II Bosporskikh chteniĭ [Cimmerian Bosporus and Pontus in Antiquity and Middle Ages: Proceedings of the 2nd Bosporan Conference], Kerch: Izd-vo Gos. Ėrmitazha, 2001, pp. 151–160 (in Russian). Tolstikov, Kuzʹmina 2011 — Tolstikov, V. P., and Yu. N. Kuzʹmina. “Novyĭ stroitelʹnyĭ kompleks v Pantikapee [A New Building Complex from Pantikapaion].” Rossiĭskaia arkheologiia [Russian Archaeology], no. 2, 2011, pp. 110–122 (in Russian). Tolstikov, Shelov-Kovedyayev 2014 — Tolstikov, V. P., and F. V. Shelov-Kovedyayev. “Bospor v pervoĭ chetverti V v. do R. Kh. Iz istorii Pantikapeia nachala klassicheskogo perioda [Bosporus in the First Quarter of the 5th Century BC. History of Pantikapaion in the Beginning of the Classical Period].” Drevnosti Bospora. № 18 [Antiquities of Bosporus. Vol. 18], edited by A. A. Maslennikov, Moscow: IA RAN, 2014, pp. 452–504 (in Russian).